Top 10 Martin Gardner Alter Egos

(Animation courtesy of Internet Anagram Server)

Material written by Martin Gardner has appeared under at least thirteen names. Here are the stories behind ten aliases or pseudonyms he used, many of which are not well known.

A more accurate title for this list is probably:

Top 10 Names Martin Gardner's Writing Has Appeared Under

(yes, this list has an alter ego too)1. George Groth (1936)

In the acadenic year 1935–1936, Martin's senior year in college, Vol IV of COMMENT ("The University of Chicago Literary and Critical Magazine") consisted of four issues. In the Nov one, Martin is billed as the Editor and Business Manager, and in the Dec, Feb, and May issues, just as Editor.

Each issue contained a one page editorial, the Feb 1936 one starting with comments on Humanism. A few pages later is a one-page short story called "Thang" attributed to George Groth. In later life, introducing it in The No-Sided Professor: and Other Tales of Fantasy, Humor, Mystery, and Philosophy (Prometheus, 1987), Martin branded it a crude imitation of Lord Dunsany. Significantly, he also identifies it as his first published work of fiction, and reveals that it was originally written for a short story writing class he took from Thornton Wilder. By then he no longer recalled why he chose that particular pseudonym. ("Groth" is pronounced "growth.")

Martin used the name George Groth again, from time to time, most famously in Dec 1983, in a New Your Review of Books piece called "Gardner’s Game with God." Amazingly, it's actually a review of his own book The Whys of a Philosophical Scrivener by Martin Gardner (William Morrow, 1983). In a recently unearthed video interview from 1994, Martin tells the amusing story of how this came to pass.

The review ends, "To put it bluntly, Gardner is a simpleminded fideist. It is impossible to imagine anyone reading his outrageous confessional...who...will not be infuriated by his idiosyncrasies."

2. Joe Berg (1937)

Joe Berg (1901–1984) was a real person, a well-known and respected Chicago magician and magic dealer. Martin ghostwrote his Here's New Magic (Joe Berg, 1937, 20 pages). It features 23 effects, including the influential "Gardner's Card Speller."

3. Humpty Dumpty Jnr (1952)

Having moved to NYC in 1947 or 1948, and tried to eke out a living as a freelance writer, placing occasional fiction and mathematics pieces, the end of 1952 was a good time for Martin. He got married, published his first real book, and started a regular job as contributing editor for Humpty Dumpty's Magazine for children. In that job he found himself writing a poem and a story each week as Humpty Dumpty Jnr, as well as devising a great deal of activities that involved paper cutting and folding, all of which would stand him in good stead in the years ahead. His time with this magazine extended well past his early days with Scientific American.

4. Polly Pigtails (1953)

Martin served as Managing Editor for this magzine for girls for several years starting with the first issue in Spring 1953. The debut welcome letter, headed "Hello, Pigtailers!" and signed "Love and kisss, Polly," breezily begins,

I'm Polly Pigtails. Of course, my last name isn't really pigtails. But everyone calls me that because I like to wear my hair in pigtails. And I don't mind, because I think it's a cute nickname, don't you?"later adding, in reference to planned contents,

"It would have comics in it, too -- and jokes, riddles, cartoons, and articles about sewing and cooking. Also articles about things to make and do, and other subjects that girls like to know about."It was a far cry from Bertrand Russell and Rudolf Carnap.

5. Martin George (1958)

Martin was very adept at crafting his message to his audience, and a puzzle he

wrote for kids in one context could be dressed up differently if he was writing

for a more adult market.

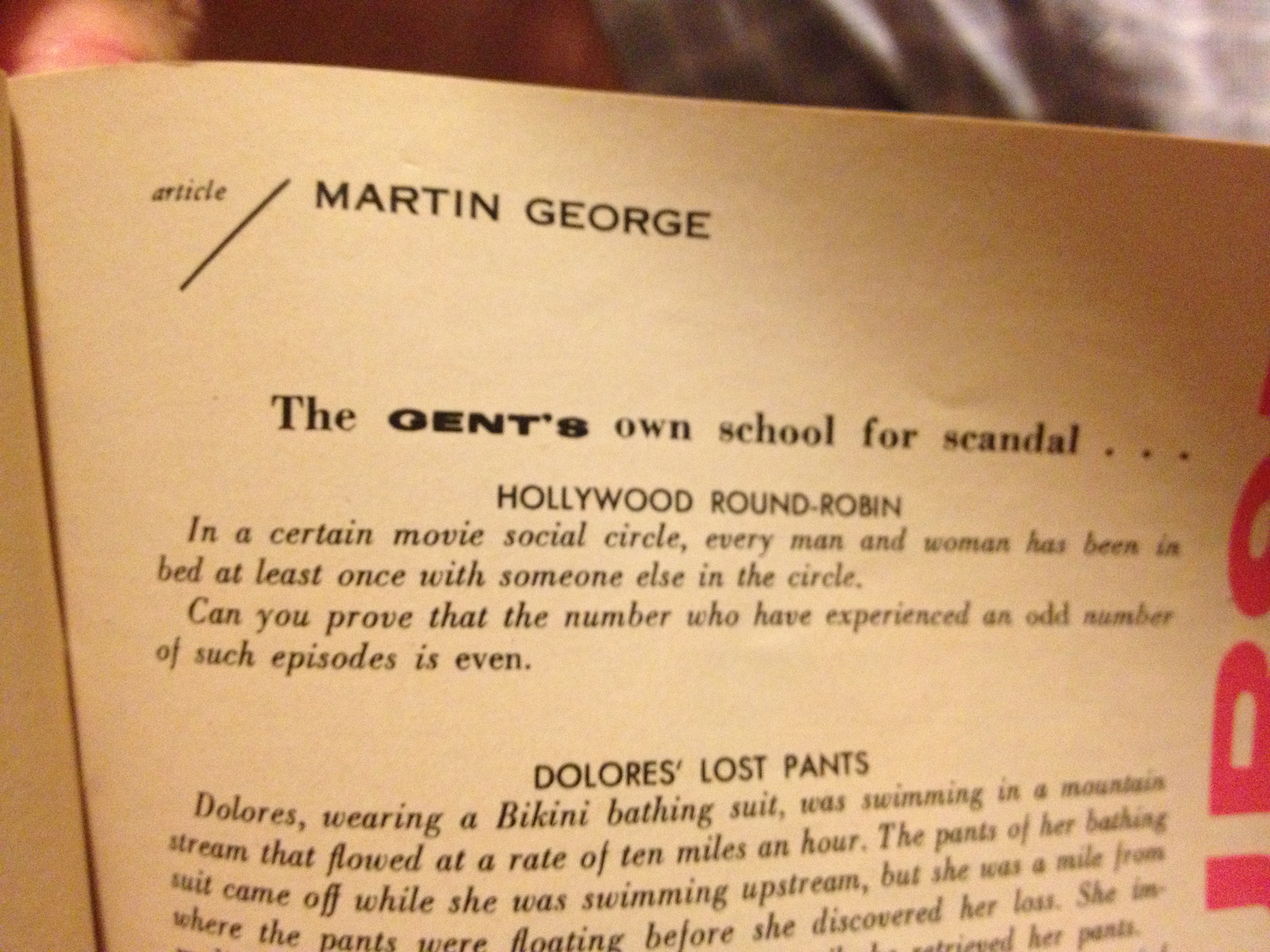

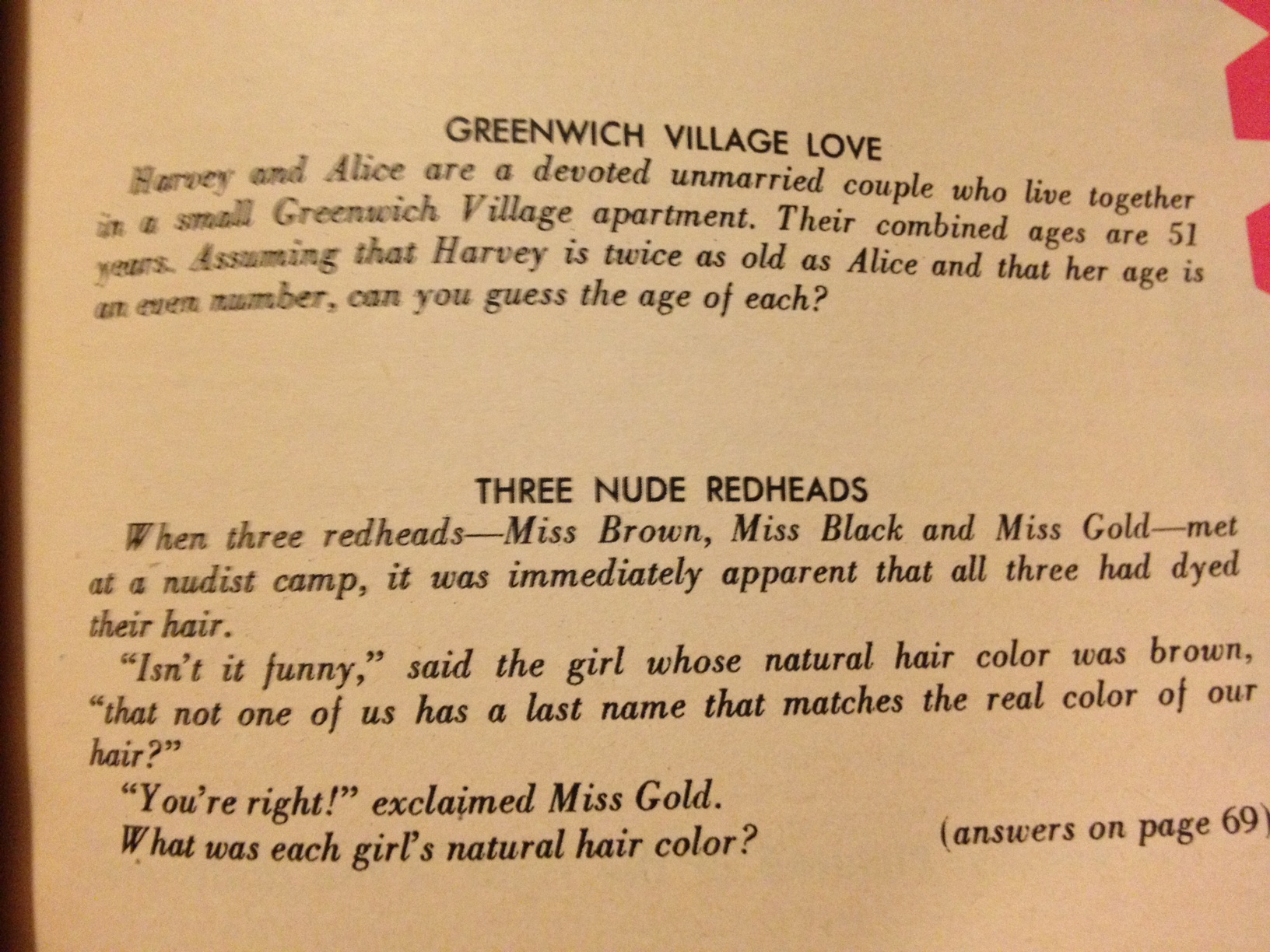

The April 1958 issue of Gent Magazine ("An approach to relaxation")

is a case in point.

It contained a one page article under the byline Martin George and the words "The GENT's own school for scandal...," featuring 6 or 7 teasers. Readers were directed to page 69 for answers.

As a careful perusal of these reveals, Martin was aiming at those who only looked at the magazine for the articles, thoughtfully dressing down some classic headscratchers about elementary graph theory and the oft-overlooked scarcity of derangements within the permutation group of three objects.

6. Dr Matrix (1960)

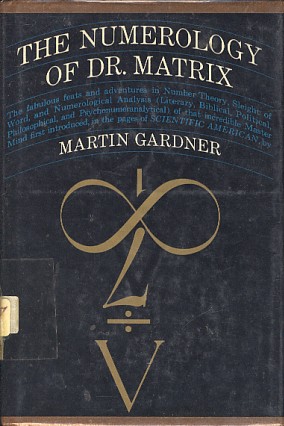

The first appearance of Martin's famous fictional character "Dr Matrix, numerologist extraordinary" was in his Jan 1960 "Mathematical Games" column, "A fanciful dialog about wonders of Numerology," in Scientific American. In addition to the amusing numerological facts which Martin's alter ego spouted from time to time here, and in subsequent columns, there was often more notable recreational mathematics on offer. These columns resurfaced in increasingly complete spin-off books in later years, as shown above.

While the Dr. Matrix material had the same source as everything else Martin wrote about—a combination of his own inventiveness and that of his wide circle of correspondents—he usually chose to pass it off as being from the fertile mind of Irving Joshua Matrix. So it may be debatable if these revelations appeared under the name of Dr. Matrix, but the tables were turned two decades later when the good doctor published a piece about Martin in a respected mathematics journal.

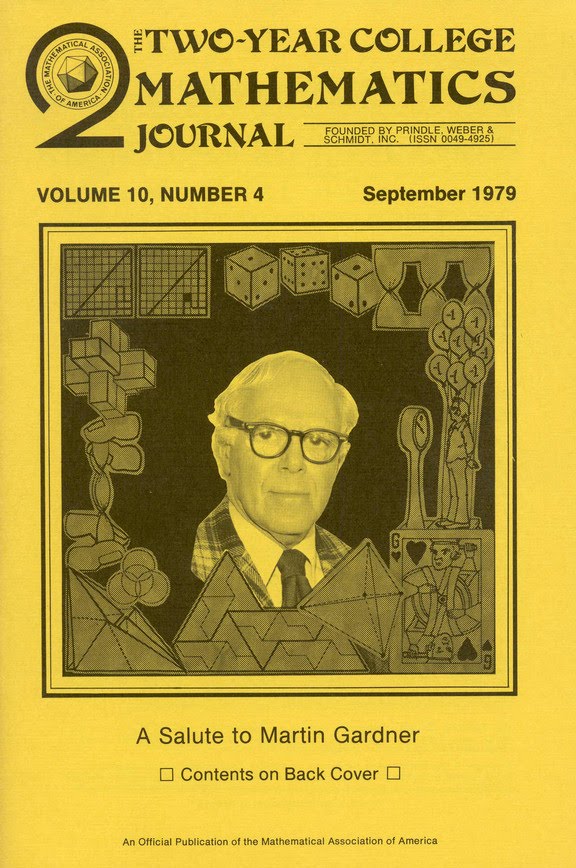

The Two-Year College Mathematics Journal (Vol 10, No 4, Sep 1979) featured "Martin Gardner: Defending the Honor of the Human Mind" (pages 227–232) by Irving Joshua Matix, in which a biography of Martin and the history of his "Mathematical Games" column in Scientific American was provided. The cover story of this issue was an interview with Martin. It would be a further decade before Martin published an article in such a mathematics journal under his own name.

7. Nitram Rendrag (1967)

In 1967, Martin published The Annotated Casey at the Bat: A Collection of Ballads about the Mighty Casey (Potter, 18 + 206 pages). It includes a parody called "Casey’s Son" attributed to Nitram Rendrag, which is Martin Gardner spelled backwards.

He used the name again for his science fiction puzzle tale "Time-Reversed Worlds" in Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine (Sep 1986, pages 20–21).

8. Uriah Fuller (1975)

Under the alias Uriah Fuller, Martin wrote Confessions of a Psychic (Karl Fulves, 1975, 40 pages) and Further Confessions of a Psychic (Karl Fulves, 1980, 69 pages), both subtitled "The Secret Notebooks of Uriah Fuller" and put out in limited circles by his friend, prolific magic writer Karl Fulves in Teaneck, NJ. These are guides to "inside secrets of seemingly incredible psychic feats"—inspired by the worldwide popularity of Uri Geller in the 1970s.

9. Armand T. Ringer (1991)

The Annotated Night Before Christmas (Summit, 1991, 257 pages) was based on Clement Moore's 1823 ballad "A Visit from St. Nicholas" (aka "Twas the Night Before Christmas"). It includes "Santa Changed His Mind" by Armand T. Ringer, of whom Martin says, "a minor poet who did not want his identity disclosed. His sequal was written at my request, and has not previously been in print."

Armand T. Ringer is an anagram of Martin Gardner, and he often used it in later years for his parodies of favorite poems, such as "Road Fog" (after Carl Sandburg's "Fog") in Martin Gardner's Favorite Poetic Parodies (Prometheus, 2001, 245 pages).

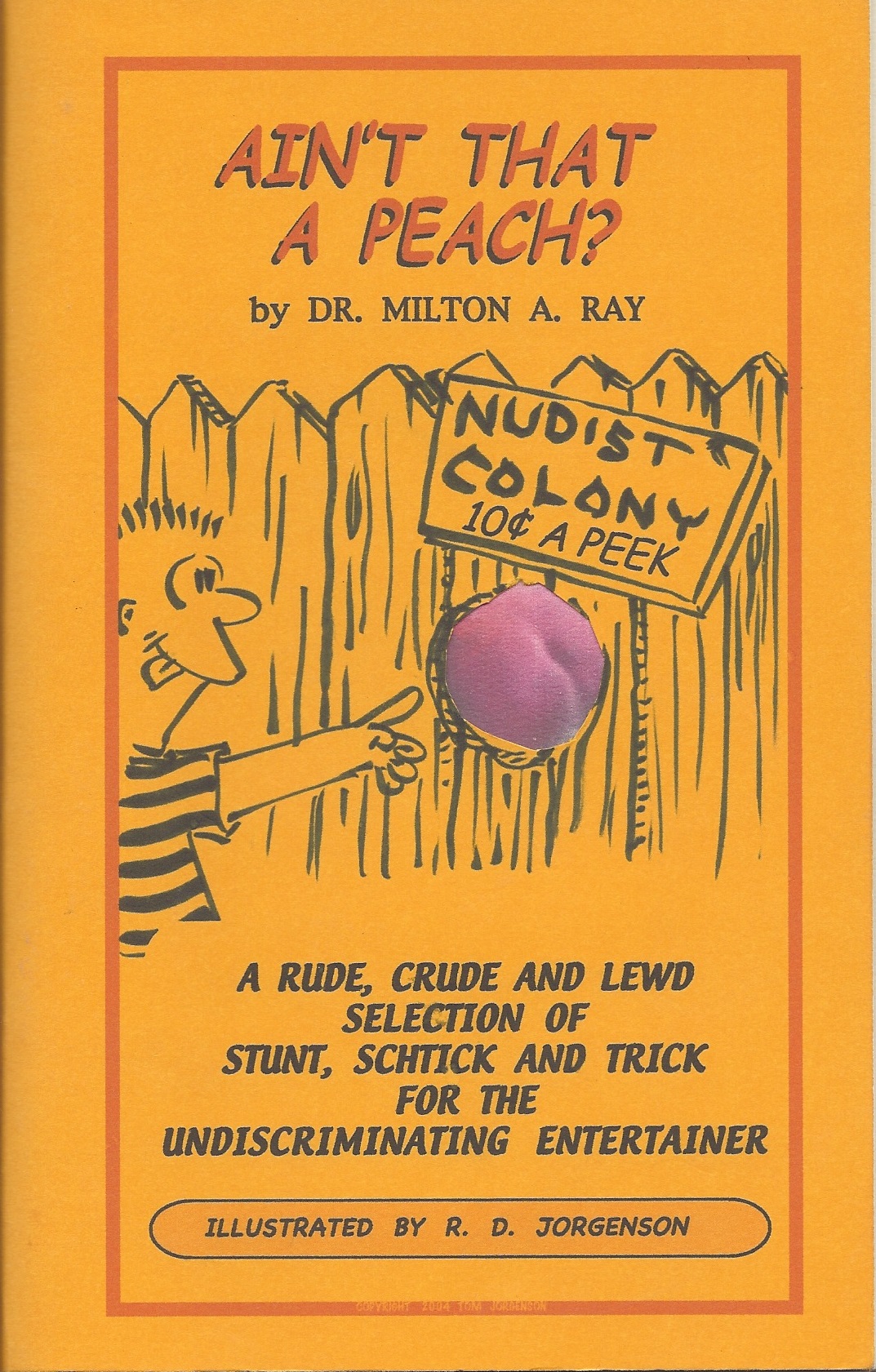

10. Dr. Milton A. Ray (2004)

Ain’t That A Peach (Jorgenson Ink, 2004, 43 pages, illustrated by Ron & Tom Jorgenson) was co-written with Mel Stover, and credited to Dr. Milton A. Ray. It's subtitled, "A rude, crude and lewd selection of stunt, schtick and trick for the undiscriminating entertainer."

The Introduction by Armand T. Ringer informs us that, "Dr. Milton A. Ray (not his real name) is a pastor of a Pentacostal church in a suburb of Atlanta. He is also an amateur magician." It goes on to explain that over the decades he and the late Mel Stover "collected blue material of such an outrageous nature that it could never be presented to family audiences..." There's a complementary note from "Phondleheine Gootch, Esq, Publisher."

The 54 items on offer are divided up into the following categories: Sight Bits,

Matches, Farts, Dollar Bills, Hands, Cards, Watches, Napkins, Words, Cigarettes,

Practical Jokes, Silverware, Unclassified, and Humor.